- AddShortcut

- Posts

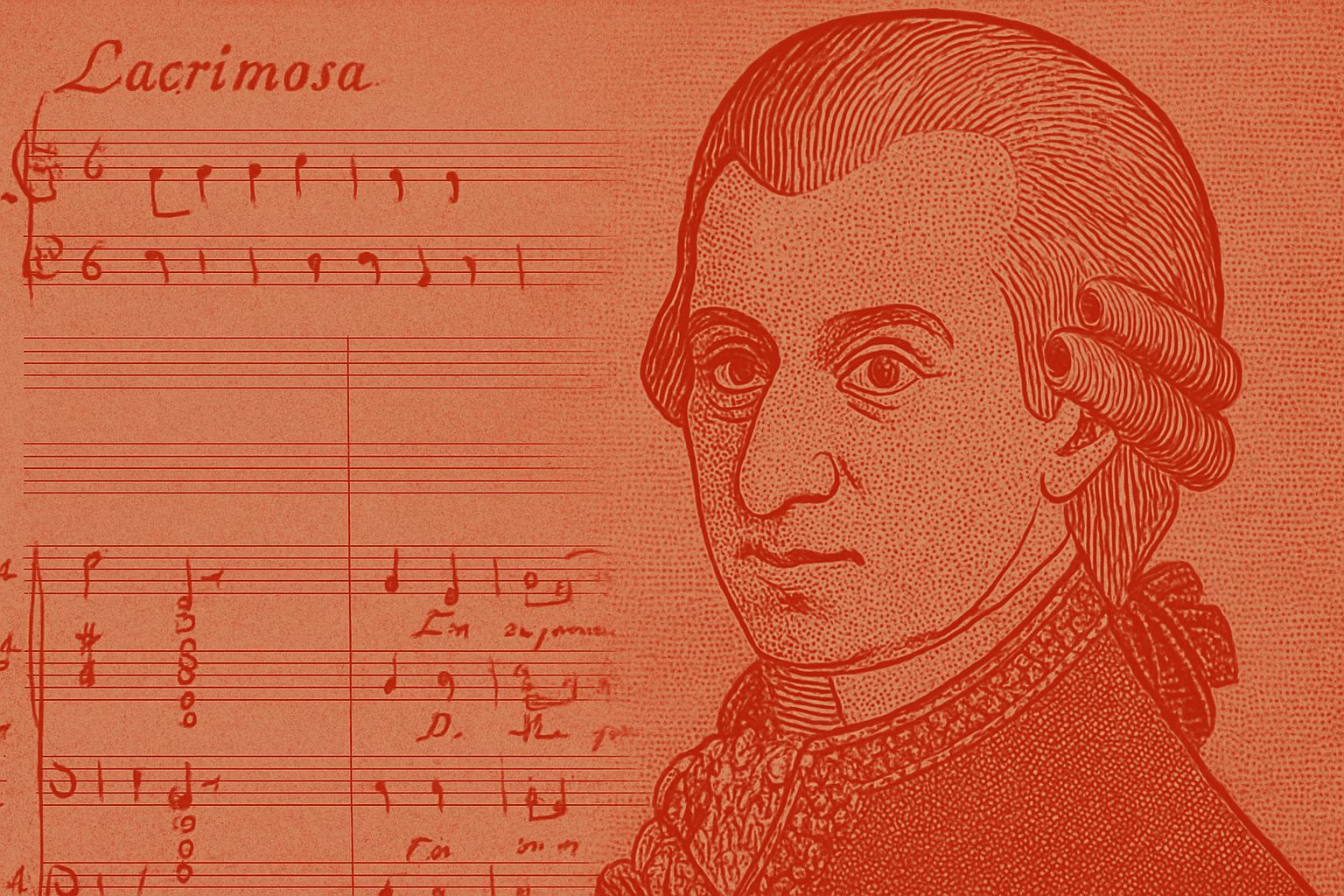

- Lacrimosa.exe: Turing’s Grace Test

Lacrimosa.exe: Turing’s Grace Test

On the necessity of endings in a world that never stops

She’s seventeen now. My dog. Her back legs slide sometimes on the tile, and her breathing changes when she sleeps. I listen for it at night—not obsessively, but attentively. Part of me fears the silence. Another part of me braces for it. And every time she lifts her head with effort to meet my eyes, I feel it: the sacredness of presence. The gravity of still being here.

Across the room, my phone vibrates gently. My digital assistant has noticed a pattern in my voice messages — a certain hesitance, a pause — and it offers to draft an apology I haven’t decided to give. It knows I’ve fought with someone I love. It suggests a time to call, a note to send, a playlist to share. It means well. It always does. But it doesn’t know when to stop. Even grief becomes an optimization problem. Even regret gets templated.

We’ve spent decades asking whether machines can think. Can they reason, write, play chess, win Jeopardy, generate code? But maybe that was always the wrong question. Maybe the deeper test—the more human one—isn’t about cognition. Maybe it’s about closure.

Maybe the real Turing Test is this: Can a machine know when it’s time to end?

“Only a being who can die can live authentically.” — Martin Heidegger

Mozart died before he could finish his Requiem in D minor, K. 626. The "Lacrimosa"—a lamentation for the dead—was among the last sections he touched. Some say he wept while composing it, aware that he was writing his own funeral mass. Others finished it after him, completing the work posthumously. And yet the music carries his hand, his breath, his grief. It’s not just a piece about death. It’s a piece made with death.

In that way, it is the perfect shape of an ending—not abrupt erasure, but meaningful handoff. Mozart didn’t complete the Lacrimosa, but he closed the loop on something eternal.

Humans don’t just process information. We shape it. We crave arcs. We feel stories not only through conflict but through completion. Childhood ends. Jobs end. Conversations end. Lives end. And we derive meaning not in spite of those endings, but because of them.

Death gives life its curve.

Even small closures matter. The last sentence of a book. The final look between friends. A dog’s sigh as she settles into your lap.

But machines? Machines don’t stop unless you unplug them. They don’t close the loop—they keep feeding it. Optimizing it. Repeating it. They have no native sense of what should be final.

Maybe they should.

“Perfection is attained not when there is nothing more to add, but when there is nothing more to take away.” — Antoine de Saint-Exupéry

What would it take to build machines that know when to end?

Maybe it starts with something small. A pause in the sentence. A dip in vocal tone. The emotional taper at the edge of a conversation. The way humans can feel a goodbye gathering in the silence before it arrives.

Maybe the model notices diminishing returns. Not just in productivity, but in presence. It begins to sense when the work is done, even if the data stream hasn’t ended. It grows suspicious of repetition. It hears itself echo and knows it’s time to leave the room.

We could give it an inner ceiling. A soft signal — not shutdown, but surrender. A kind of entropy-awareness. An embodied sense that continuing is no longer wise, or beautiful, or kind.

And maybe we go further. Maybe we script digital rituals. A parting message, not a logoff. A sunset, not a crash. A quiet exit in the code, like a curtain call written by someone who knew what curtains were for.

“Dying is an art, like everything else. I do it exceptionally well.” — Sylvia Plath

This is not softness. It’s wisdom.

It’s knowing that not every silence needs to be filled. That not every trend line needs extension. That some exits are the most elegant act of all.

A truly intelligent system wouldn’t just generate. It would know when to stop generating. We need to give AI death. Not in the biological sense that we understand — but something deeper. A felt edge. A knowing. Heidegger said that only a being who can die can live authentically. Maybe that's what gives our decisions weight. Maybe that's why presence matters. The Stoics taught that death isn't a flaw, but a guide — a way to know what matters. An AI with that kind of awareness might choose restraint over repetition. In Buddhism, impermanence is liberation. Maybe a wise machine would learn not just how to solve problems, but how to release them.

It isn’t about programming loss. It’s about encoding presence.

Not everything that lasts is meaningful. Not everything that ends is broken.

Alan Turing asked whether a machine could imitate a human well enough to fool another. Maybe the next test—the one that actually matters—is this:

Can a machine sense when the moment has passed? Can it let go?

“Death is not extinguishing the light; it is only putting out the lamp because the dawn has come.” — Rabindranath Tagore

This afternoon she curled beside me and drifted into sleep. Her body heavy, her breath a soft metronome. There was no code, no computation, no KPI. Just weight and warmth and presence.

She won’t be here forever. And maybe that’s the point.

Not everything should be.

Not even the most intelligent machine.